- Home

- Kate Sedley

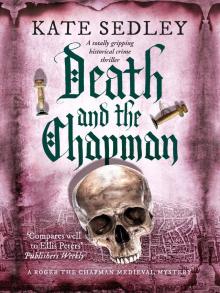

Death and the Chapman Page 3

Death and the Chapman Read online

Page 3

‘It’s beautiful. Look, Marjorie! I shall use it to trim the neck of my wedding gown. I’ll take it. All of it.’ She did not even ask the price. ‘Pay the man, Marjorie. I’ve no money on me. Father will give it back to you when he comes home.’ Marjorie, none too pleased, as I could tell, shuffled away to get her purse while Alison waved me back to my seat at the table. ‘You might as well finish your meal.’

I thanked her politely, repacked the rest of my stuff, told Marjorie the cost of the ribbon and pocketed the money before sitting down again to my stew, which had now gone cold and congealed on the plate. It looked grey and unappetizing and I no longer fancied it, so I pushed it to one side and finished my ale. I was just about to say I must be going, when Alison Weaver drew up another stool and sat down beside me.

‘What were you both talking about,’ she demanded accusingly, ‘when I came in?’

Chapter Three

There was an uneasy silence, and I could see that Marjorie Dyer was debating with herself whether to tell the truth. I drained the dregs of my ale and read the little rhyme carved into the wooden base of the mazer. ‘If you would a Goodman please, Let him rest and take his ease.’ A fine sentiment, no doubt, but not one many Goodwives were prepared to abide by. And, indeed, why should they? Most of them worked hard from sunrise to sundown. I know my mother did. I’m not talking about the nobility, you understand, or even Alderman Weaver’s daughter. At this point in my life, I knew very little about such women.

Marjorie cleared her throat, but her mistress was quicker. ‘You were talking about Clement, weren’t you? You know Father doesn’t like you discussing our business with strangers! You’re a gossip, Marjorie, and you know what happens to gossips. They get ducked in the pond.’ The girl then seemed to relent, but I could see by the expression on Marjorie’s face how deeply she resented the reprimand, particularly in front of me. Once again, I wondered what the real relationship was between her and the family. She seemed, on one hand, to hold the privileged position of an old and trusted retainer, but on the other to be everybody’s whipping-boy. Alison Weaver went on: ‘Oh well, I suppose there’s no harm done. How much have you told him?’

‘Only that Master Clement disappeared last winter in London.’

‘And hasn’t been heard of since,’ I added. ‘Other than that, I know nothing, so you need have no fear that I shall be bruiting your family business abroad. I’ll be on my way.’

I half rose from my stool, but the girl waved me down again. She had an air about her of one accustomed to being obeyed, and in those days I was unused to standing up for myself. She looked at me with curiosity.

‘You don’t talk like any chapman I’ve ever met. Who are you?’ So I recounted my life’s history once more and was gratified to note that by the end of it she was regarding me for the first time as though I were a human being and not a part of the furniture. I could tell, too, that she liked what she saw. I was a good-looking youth at that age, even if I do say so myself. When I’d finished speaking, she rested her elbows on the table and propped her chin between her hands; little hands that gave small, fluttering movements like captive birds.

‘Would you care to hear the whole story,’ she asked me, ‘about my brother’s disappearance?’

‘If you would care to tell it me,’ I answered gravely.

‘What do you think, Marjorie? Would Father mind?’

Marjorie shrugged her plump shoulders. ‘He might, but he’s not here, is he? And won’t be for an hour or two yet. He’s gone to a Guild meeting, and afterwards to a service at the Temple chapel.’ She added for my benefit: ‘It’s the Weavers’ chapel, dedicated to St Katherine, their patron saint.’

Alison copied the housekeeper’s shrug. ‘In that case, what he doesn’t know won’t hurt him.’

I have never ceased to marvel, all my life, at the pragmatism of women: I think they are born without scruples. Nevertheless, I have been thankful for it on many occasions, as I was thankful for it then, because my curiosity had been aroused, and to leave with it unsatisfied would have been like denying a man dying of thirst a drink. And as though she read something of my thoughts, Marjorie Dyer asked: ‘Shall I pour us all some ale?’

Her mistress nodded. ‘And open the door a little more. It’s close in here with the heat of the fire.’

The housekeeper took my empty mazer and reached two more down from a shelf, filling all three from the cask of ale. Then she stood the door wide, letting in the fragrant scents of the garden. The afternoon had turned extremely warm and there was a faint shimmer of heat in the air. The light quivered as bright as a sheet of pressed metal, and the faint, far cry of a bird was, for a moment, the only sound on the still, spring air. Then the noises of the city seeped back, like a slowly rising tide.

Alison Weaver sipped her ale and fingered the coral rosary around her wrist. ‘I don’t know where to begin,’ she said.

‘Begin with your journey to London. There’s nothing much to tell before that.’

Marjorie, I thought, spoke with unnecessary sharpness, but looking at her, I could see that she was upset. Clement Weaver had probably been her favourite; less imperious, perhaps, than his acid-tongued sister. I had a mental picture of a sweet, soft-spoken boy, deeply affected by his mother’s death.

Alison nodded, sipped more ale, then resumed her former position, elbows on the table, chin propped between her hands. ‘It was before Christmas, last year,’ she began, ‘around All Hallowstide…’

She had recently become betrothed to William Burnett, the son of another of Bristol’s aldermen and a fellow member of the Weavers’ Guild. The Burnetts, I gathered, were even more well-to-do than the Weavers themselves, owning up to a hundred looms in the suburb of Redcliffe and claiming kinship with a nobleman who lived in the village of Burnett, some miles outside the city. It was an alliance, therefore, to gratify the one family more than the other, and Alderman Weaver was determined that no expense should be spared on arrangements for the wedding. In particular, his daughter’s bride-clothes should be the best that money could buy and Bristol merchants were deemed unworthy of providing the necessary materials. Alison was despatched to London, in the company of Clement, to stay with her uncle and aunt, the Alderman’s brother and his wife. John Weaver, also employed in the cloth trade, had elected many years previously, on the occasion of his marriage, to try his fortune in the capital and was now, it seemed, nearly as rich – although, gratifyingly, not quite as rich – as his elder brother. He and his wife lived in the ward of Farringdon Without, which, so Alison informed me, taking pity of my self-confessed ignorance of London and its byways, included Smithfield cattlemarket, the Priory of St Bartholomew and the Temple and its gardens, which ran down to the River Fleet. It was, moreover, within easy reach of the Portsoken ward, where the weavers had their dwellings.

‘You were both to stay with your uncle and aunt?’ I queried, when Alison paused for a moment. ‘Both you and your brother?’

But this, apparently, was not the case. John Weaver and his wife, Dame Alice, had two grown sons, one of whom was married and had not yet left home to set up on his own.

Although a truckle bed could therefore be offered to Alison, there was no room for Clement. He was to lodge, as the Alderman himself did when in the capital, at the sign of the Baptist’s Head in Crooked Lane, off Thames Street; an inn owned and run by his old friend from Bristol, Thomas Prynne.

‘You remember, I told you,’ Marjorie said with a nudge, ‘he was landlord of the Running Man before he decided to try his luck in London.’

I recollected and nodded. ‘You were reluctant to recommend the inn now that Thomas Prynne is no longer there.’

‘A good man,’ Marjorie confirmed. ‘Greatly liked and very much missed in Bristol. He and the Alderman were close friends. They grew up together in Bedminster village.’

Alderman Weaver had plainly outstripped his boyhood companion and, by the same token, was a self-made man, not the heir of inherited wealth

as his children were. Children? Or child? I glanced again at Alison, which prompted her to continue.

‘As I was saying—’ here she darted a look at the housekeeper as though resentful of being interrupted ‘—Clement was to stay at the Baptist’s Head.’ She conceded: ‘Marjorie’s right about Thomas Prynne. My father has known him all his life. When we were little, Clement and I used to call him Uncle Thomas, although my mother objected. She was a de Courcy, you see.’ She spoke as if this explained everything, as in some ways it did. The name indicated descent from the old Norman aristocracy, and the Alderman, on his way up, had no doubt considered such a marriage advantageous. I wondered idly how much dowry the lady had brought him. I suspected little. My guess was an impoverished family with pretensions, but fallen on hard times, forced to ally itself with ‘new’ money. I speculated on the probable happiness of such a union. Alison continued, recapturing my wandering attention: ‘Father would never let Clement stay anywhere else in London. And especially not on that occasion. It was absolutely necessary that my brother should lodge with someone he could trust.’

I took another gulp of ale. ‘Why?’ I asked, although I could already guess the answer.

Alison Weaver twisted the black and gold cramp ring on her finger. ‘He was carrying a great deal of money on him, money for me to buy my bride-clothes with.’

‘How much?’ I asked, forgetting in my eagerness for details that I was a lowly chapman and she the daughter of an alderman. I felt Marjorie kick me under the table.

Alison, however, was too wrapped up in her story to notice my impertinence, or to make anything of it if she did. She must, during the past months, have gone over and over the events in her mind.

‘A hundred pounds,’ she said in an awed voice. ‘One hundred and fifty marks. Some of it, mind you, was for payment to the Easterlings at the Steelyard. My father told me afterwards that he had unintentionally overcharged them for a consignment of cloth and had instructed Clement to reimburse them while he was in London.’

‘A great sum of money for a young man to be carrying,’ Marjorie interrupted. ‘It was asking for trouble if you want my opinion.’

‘Nobody does!’ her mistress replied tartly. ‘And in any case, no one knew how much he was carrying, not even me. There was no reason for anyone to suspect that he had such an amount about his person.’

‘Footpads and thieves,’ I pointed out gently, ‘take their chances. Anything and everything is grist to their mill. Two marks are as much worth stealing as twenty. And if the haul turns out to be a large one, that’s simply their good fortune.’

‘Precisely what I said!’ Marjorie nodded sagely. ‘I only wish I’d known how much money the Alderman had entrusted to Master Clement. I should have tried to talk him out of it, or persuaded him to go himself. A young man on his own, carrying a purseful of gold, is asking for trouble! And in an evil city like London!’

Alison jumped to her feet, the hazel eyes blazing. The green flecks seemed to disappear, swamped by her anger.

‘Shut up, Marjorie! Shut up! It’s easy enough to be wise after the event.’

I felt this to be a little unfair. Marjorie, had she been in possession of all the facts, would, according to her own account, have been wise before the event, and whatever had happened to Clement Weaver might have been prevented. I agreed silently with her that the Alderman had been foolish, and in consequence felt obliged to take her part.

‘I have heard,’ I offered tentatively, ‘that London is a very dangerous place.’ I noticed that since we had begun talking, the light had changed. Through the open kitchen door, the trees and distant rooftops, visible above the garden wall, were painted with sudden sharp brilliance against a sky which had faded from blue to pearl-grey. The day which had been so fine, would end in rain, and as though to confirm this impression, from far off came a faint rumble of thunder. I made to rise again. ‘I should be on my way. I have my living to make and lodgings to find before the storm breaks.’

Alison turned her small, neat head in my direction. ‘Sit,’ she ordered. ‘You haven’t heard the end of the story.’ She added on a suddenly fretful note: ‘Don’t you want to?’

‘Very much.’ And that was the truth. ‘It’s just that I’ve sold nothing today beyond the ribbon you bought off me. I need money if I’m to sleep dry and safe tonight and not under a hedge.’

She resumed her seat at the table, willing me to do the same. Against my better judgement, I complied. ‘You can sleep here tonight,’ she said, astonishing both Marjorie and myself, ‘by the kitchen fire. I’ll speak to Father about it when he comes home.’

I realized afterwards, looking back, that her brother’s disappearance must have occupied most of her waking thoughts and possibly many of her dreams as well. It had no doubt been the main topic of conversation between herself and all those close to her for the last five months. They had talked around it in circles until they had nothing new to say on the matter. Each one proffered the same jaded point of view. She needed a fresh mind, fresh thoughts, before she could finally accept that there was no solution to the puzzle; that her brother was gone and would probably never be seen alive again. Because I have to admit, from what I had already heard, that that was the most likely outcome. A wealthy young man, set upon and murdered for his money, his body disposed of in the nearest river, was that so unprecedented? It was one of the hazards of everyday life. And didn’t the Scriptures tell us that man born of woman had but a short time to live? Murder, rapine, famine, plague, they were all God’s instruments.

With a start, I realized that I was thinking as I had been taught to think, expected to think, by the monks who had been my teachers. It was partly to escape their abject acceptance of the inevitability of Divine Will that I had decided against taking my final vows.

‘Your father will never permit of his sleeping here,’ Marjorie protested. ‘The chapman should be gone before the Alderman returns.’

‘I’ve told you, I’ll speak to Father.’ Alison dismissed the housekeeper’s objections and turned to me. ‘Well? Will you stay? The price I paid for that ribbon is sufficient, I should have thought, to let you eat for at least a couple of days.’

‘That I paid,’ Marjorie muttered under her breath, but not so low that her words were inaudible. I expected her mistress to fly into another fit of passion, but Alison ignored her, raising her eyebrows once again at me.

‘If you’re certain that your father won’t mind, I should be grateful for the chance of a warm fire and decent food.’ The first drops of rain had started to fall and I could hear their faint pattering on the leaves of the trees. The air was heavy and windless, but the tiniest of soughing noises among the branches indicated a rising breeze. It could be a cold wet night.

‘Leave Father to me.’ Alison spoke with authority. ‘Now, what point had we reached in the story?’ And without waiting for, or needing, a reply from either of us, she continued: ‘The circumstances were not what you think. Nor what Marjorie has led you to believe. My brother was not roaming the streets of London with such an amount of money in his pocket. We left Bristol on All Hallows’ Day, and two of our men, Ned Stoner and Rob Short, went with us. My maid Joan rode pillion behind Ned. We spent three nights on the road and my father hired four other men to go with us as far as Chippenham. When we neared London, my uncle sent two of his servants as far as Paddington village to accompany us into the city and guide us to our destinations.’ She paused for breath, and once more there came the distant rumble of thunder, but closer this time. The noise of the rain increased.

‘You were well protected, then,’ I said.

She nodded. ‘For most of the time. And even when there were only the five of us, we travelled with a party of merchants whom we had met at one of the inns where we stayed. My father advised us to do that, and we obeyed him.’

‘So?’ I prompted, when she seemed to have fallen into a reverie. ‘What happened when you finally reached London?’

‘What? O

h! It was raining hard and had been for the most of the day, so my uncle and aunt had sent their coach for me and my maid. But Clement’s mare, Bess, had cast a shoe and it was agreed, in order to save time – it was late afternoon by now and beginning to get dark, you see – that he should ride in the coach with us, and that Ned would return to Paddington the following morning to collect Bess from the smithy. We therefore went first to the Dowgate Ward to let my brother alight, before continuing to Farringdon. He got out at the corner of Thames Street and Crooked Lane.’

‘Alone? Why didn’t Ned or Rob remain with him?’

‘Rob was leading my horse and was to lodge at my uncle’s with Joan and me. Ned was to stop with Clement at the Baptist’s Head but my uncle’s two men seemed anxious for his company. They were full of stories of bands of armed men who roamed the city streets, preying particularly on women, and my brother urged Ned to do as they asked. He could rejoin him later, Clement said. Besides, the inn was only a little way down the lane, within sight of where we left him.’ Alison dipped a forefinger in the remains of her ale and drew a rough map on the table. ‘This is Thames Street,’ she said, ‘and this—’ she made another damp line at right-angles to it ‘—is Crooked Lane, running down to the wharves and the river. Here, at the corner where we dropped him, is another inn called the Crossed Hands, and the Baptist’s Head is a little further down on the opposite side. We could see the sign and the lanterns hung on the wall. It was only a few steps for him to go and we did not wait. My uncle’s men were anxious to be home before curfew and I think we were all looking forward to our beds. I leaned out of the coach to wave goodbye. Clement was standing, huddled inside his cloak, immediately beneath a torch fixed high up, near an upstairs window of the Crossed Hands inn. He waved back, then made an impatient gesture to speed us on our way. I drew the curtains of the coach and settled back into my seat for the remainder of the journey. I remember remarking to Joan how tired I was and that I should be glad to be safely indoors. It was a wild night and I recall how the torches guttered when my uncle and aunt came out to greet us. Ned returned at once to Crooked Lane and the Baptist’s Head.’ Her voice caught in her throat. ‘But he never found Clement. He wasn’t there. Thomas Prynne said he’d never arrived.’

Death and the Chapman

Death and the Chapman