- Home

- Kate Sedley

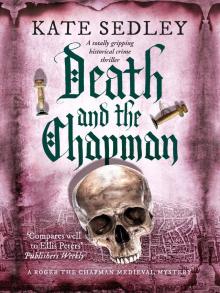

Death and the Chapman

Death and the Chapman Read online

Death and the Chapman

Cover

Title Page

Part One May 1471

Bristol

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Part Two September 1471

Canterbury

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Part Three October 1471

London

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Next in Series

About the Author

Also by Kate Sedley

Copyright

Cover

Table of Contents

Start of Content

Part One

May 1471

Bristol

Chapter One

In this year of our Lord 1522 I am an old man. I’ve lived through the reigns of five kings; six, if you count young Edward. By my reckoning, I’m three score years and ten, the age, so the Bible tells us, which is man’s allotted span on earth, and when my time comes, I shan’t be sorry to go. Things aren’t what they were, as I keep telling my children and grandchildren. And, come to think of it, as my mother told me.

‘Things aren’t what they were when I was a girl,’ she’d say, sweeping hard with her broom and sending the dust and bits of dead rushes flying out of doors, for all the world as though she were trying to sweep modern manners and modern thinking out with them.

I remember that little house in Wells as plainly as though I’d been living there yesterday. My father, on the other hand, is a shadowy figure. Not surprising, really, because he died when I was barely four. He was a stone carver by trade, and very highly thought of, according to my mother. And it’s true that when he died, following a fall from some scaffolding while working on the ceiling of the cathedral nave, the Bishop – I forget his name, but he was the one before Robert Stillington – paid my mother a small pension out of his own pocket. I think, really, that’s what started all her ideas, wanting me to have an education, to be able to read and write. Which is why she entered me as a novice with the Benedictines at Glastonbury.

Poor woman, she could never see that I wasn’t cut out for the monastic life. I liked the outdoors. I liked being my own master. And I’d absolutely no ear for music. My tuneless chanting at the daily offices would drive my fellow novices mad and was only one of the many reasons why they were glad to see the back of me. My good health, which I’ve kept all my life until recently, was another. The other monks and novices were constantly in and out of the Infirmary, especially in winter, but I don’t recall ever having visited it once in all the time that l was at Glastonbury. And I’ve always had excellent teeth, never suffering much from toothache and its attendant ailments. One or two have gone now, of course, and a couple of others give me trouble when the wind’s in the east, but what can you expect, at seventy?

But the real reason I left the abbey and took to the road, after the death of my mother, was more fundamental than being resented by my fellow inmates. It was between me and God; and the abbot, who was a wise and tolerant man, understood that. It’s not that I doubt the existence of some other world, some hereafter. It’s simply that I can never be quite certain that Christianity holds all the answers. Often walking through the oak and beechwoods, particularly at dusk, I’ve experienced something of the power which the ancient tree gods exercised over the minds of our Saxon ancestors. Those gnarled, arthritic branches, reaching towards me through the gloom, bring to life some race-memory. More often than I care to admit, I’ve glanced fearfully over my shoulder, expecting, against all reason and faith to see the figure of Robin Goodfellow or Hodekin or the terrible Green Man.

Mind you, this is a heresy I’ve kept to myself. I’m not such a fool as to say it out loud. And especially not now, when Pope Leo has just given King Henry the Eighth the title of Fidei Defensor for his written answer to the German monk, Martin Luther. And I’m only committing pen to paper, because I feel I haven’t all that much time left to me. Why do I feel like that? Nothing specific. Nothing I can put my finger on. Just a general feeling of malaise, a reluctance to get up in the mornings, a shortness of temper with my daughter, my sons and their children. I’m tired of modern, forward-thrusting youth with their modern, forward-thrusting ways, and their unshakable conviction that Henry Tudor and his son, our present king, rescued this country from the grip of a monster. It’s my privilege to have met our late King Richard, even to have been of some use to him, God bless him!

But, nowadays, that’s another heresy, and probably worse than the first one. The Richard people talk about now is a hunchbacked monstrosity, steeped in blood and evil. But that isn’t the man that I remember, though I’ve no intention of writing a political tract: just a record of my early life, which in many respects was a strange one.

When my mother died, before I’d taken my final vows, and I felt free to flout her wishes and leave the abbey, I decided to become a chapman. An unlikely decision, you might think, for a lad who could read and write, hawking silks and laces and suchlike around the countryside. But after those years of being cooped up, hemmed in by rules and regulations, I needed the freedom. I needed to be my own master. I wanted to see different parts of this land of ours, which I knew only very slightly by reputation. Above all, I wanted to see London.

I find that strange now, back here in the heart of Somerset, looking out over the shadowed valleys and thickly wooded hills, the scent of the warm-smelling earth strong in my nostrils. But in those days, London was my goal, the place where I was to make my fortune. I never did, of course. I wasn’t cut out to be another John Pulteney or Richard Whittington. But if I didn’t make much money, I did find that I had a talent in another direction. I found that I was good at solving puzzles, unravelling mysteries that baffled other people. And really, that’s what these memoirs of mine are all about, in the hope that one day, when I’m dead, my children will be interested enough to read them.

It all began with the case of the disappearance of Clement Weaver, a young man I’d neither seen nor heard of that May morning in the year of Our Lord 1471. I hadn’t long been on the road in those days. My mother had died the previous Christmas, and her thrift had meant that she was able to leave me a small – a very small – sum of money. With it, I had bought my first stock from an old pedlar who was giving up the road to spend his dying years as a pensioner of the monks at Glastonbury, although I was unable to purchase his donkey. But I was young and strong, big and tall for my age, with broad shoulders, and quite capable of carrying my pack on my back. So I set off, full of confidence, walking up from Wells towards Bristol, stopping to sell my wares in the villages through which I passed. I spent May Day at Whitchurch, helping the villagers to bring in the may and then going to church to celebrate the feast of St Philip and St James; for me, a satisfying blend of the ancient tree-worship of our Saxon forebears and the demands of Holy Church which rule all our lives. I approached the walls of Bristol on 2 May.

* * *

I could tell that something untoward was happening while I was still several hundred yards from the Redcliffe Gate. There was an unusual amount of activity, with armed men coming and going, and a crescendo of noise which permeated the town walls like water seeping through a dam. Near the church of St Mary, tents and all the debris of men who had spent a coupl

e of nights in the open, indicated a military camp which was now being struck, the men scurrying about like ants, suggesting that they were in a hurry to be gone. Sudden orders to move on? I wondered. There was more than a hint of panic in the air.

As I neared the gatehouse, the town hermit, ragged, filthy and stinking to high heaven, scuttled out of his hovel to survey me, begging bowl hopefully extended. One glance, however, at my youth, my patched and mended clothes, caused his weatherbeaten face to crumple with disappointment. He muttered something into his matted beard and disappeared again, quickly. Bristol was – still is – a very rich city, second in importance only to London, and he had no time to waste on the obviously poor and needy.

As I pushed my way into the gatehouse, the noise became deafening. It sounded as though an army were on the move. The watchman on duty was a surly, heavily pock-marked man whose naturally high complexion was now a fierce and dangerous red as he struggled to cope with, and control, the increased traffic of the archway. As well as the farmers and tradesmen going about their daily business, the roads were becoming increasingly choked with pilgrims on their way to Canterbury or Holywell or Walsingham, many of them stopping en route to see the sights of Bristol. And, added to this, soldiers continually tramped back and forth between the castle and the camp outside the city.

‘What’s happening?’ I asked the watchman.

It was not the best moment I could have chosen. The man was in the middle of an acrimonious discussion with a big, raw-boned farmer concerning the amount of toll the latter had to pay on the sheep he was driving in to market. He paused just long enough to vent his spleen on me.

‘Soldiers!’ he spat. ‘That’s what’s bloody ’appening. Eating our victuals, drinking our wine and leaving us to pay the bleedin’ bill!’ And he turned back to the farmer, who had had time to get his second wind and was more convinced than ever that he was being overcharged.

I left them to it and stepped out into Redcliffe Street on the opposite side of the gate. By the time I reached the High Cross in the centre of the town, progress was growing extremely difficult. The frequent paradings of foot-soldiers and the forays from the castle of mounted men-at-arms forced all other traffic almost to a standstill. And then, while I hesitated, wondering whether to start knocking on doors immediately or to find myself a meal at one of the inns – my big frame needed constant sustenance, another fact which had marked me out as unsuitable for monastic life – I suddenly found myself shoved unceremoniously to one side as a party of horsemen cleared a passage for two women riding in their midst. Along with the rest of the enforced spectators, I stared at them curiously. The older of the two looked neither to right nor left, imperiously oblivious of the tide of common life which surged around her. The thin, bitter face, seamed with wrinkles, showed the marks of suffering, and when a voice behind me muttered: ‘That’s Queen Margaret,’ I realized with a shock that this must be Margaret of Anjou, the wife of King Henry the Sixth. But what was she doing here, in Bristol?

My gaze switched to her companion, a slender slip of a girl, who looked too fragile to control the big brown bay on which she was mounted. She wore unrelieved black and was obviously in mourning. A sudden breeze, whipping up High Street from the Backs, momentarily lifted the veil from her face to reveal a glimpse of deathly pallor and jutting bones, in which the eyes were just two dark smudges. Almost at once, she raised a gloved hand and shrouded herself again in the clinging draperies. Then she was gone, along with the rest of the little cavalcade, clattering down Corn Street towards the bridge at the far end, which spanned the River Frome. We all stared after the dwindling figures for a moment, then stirred, grumbling about the delay before continuing with our business. Returning to the debate which had been my chief preoccupation before the interruption, I decided that the rumblings of my stomach merited my undivided attention, and asked the woman standing next to me for directions to any inn where they served a reasonable meal and did not give short measure on the ale.

She was a plump, homely body, not, I decided, quite as old as the network of fine wrinkles around the eyes at first indicated. The eyes themselves were dark brown, slightly opaque, conveying an impression of secrecy. But when she smiled, as she did after having carefully surveyed me from head to toe, they twinkled, giving her face an altogether pleasanter expression than it had worn hitherto. Her plain dress of homespun and home-dyed black broadcloth, and a complete absence of jewellery, indicated her lowly status and broke none of the sumptuary laws which Parliament so regularly pass and which we English as regularly, ignore. The wisps of hair protruding from beneath her green woollen hood showed flecks of grey among the faded brown.

‘Looking for somewhere to eat, are you?’ she asked, sucking her lower lip and giving me the impression that she was playing for time while other thoughts took precedence in her mind. ‘Well, let me see… There’s Abyngdon’s, behind All Saints’ church, just down the road a bit, off Corn Street. Used to be called the Green Lattis, but that’s neither here nor there. Then there’s the Full Moon, but that’s usually crowded by midday with visitors to St James’s priory. There’s the White Hart at the end of Broad Street. Or the Running Man… On second thoughts, I wouldn’t recommend that one. It was all right when Thomas Prynne was landlord – great friend he was, and still is, of my master – but he went to try his luck in London. Owns the Baptist’s Head in Crooked Lane, off Thames Street…’ Her voice tailed away and she stared into the distance, as though contemplating something there that she would rather not see. It was with a considerable effort that she pulled herself together and once more gave me her attention. ‘A pedlar, are you?’

‘Yes.’

‘Where have you come from? I’d say you’re local, by the sound of you.’

‘I was born in Wells.’ I saw no need, at that point, to enlarge any further. ‘Thank you for your directions. I’ll try Abyingdon’s as it’s nearest.’

‘Hold on.’ The woman laid a plump hand on my arm and I recall thinking that her grip was surprisingly tenacious. ‘It must be nearly midday. You’re late for dinner. Ours was over nearly an hour ago. But if you like to accompany me while I run my errand, you can come home with me afterwards and I’ll make sure you’re fed. We keep a good table in Broad Street. Nothing’s too good for an alderman of Bristol.’

I hesitated, suddenly unsure of my ground. She spoke with sufficient authority to make me wonder if perhaps I had been mistaken in assuming her lowly status.

‘The Alderman is your husband?’ I ventured.

She gave a deep-throated chuckle. ‘Get away with you! Do I look like the wife of an Alderman? No, of course not! He’s my master. I keep house for him and his wife and… and his children.’ There was a slight hesitation, as though she were about to amend what she had said; then, evidently thinking better of it, she took my arm again, this time tucking one plump hand into the crook of my elbow. ‘If you’ll give me your support as far as Marsh Street, we’ll get on all the faster. I’m not as young as I was.’

We set off along Corn Street, dodging the piles of filth in front of the houses and the mounds of offal outside a butcher’s shop. There were plenty of pigs and goats, too, to impede our progress; they had no business, legally, to be kept within city limits; but the good citizens of Bristol ignored this regulation in the same way that people of other towns up and down the country ignored it. If there’s one thing I’ve learned in my life it’s that the English see every law as a challenge, either to be circumvented or broken. I think the thing I remember most about that walk is the clamour of the bells. We’d heard them at Glastonbury, of course, sounding for the different offices of the day, but this was my first time in a city, and I’d never heard so many ringing all together; tolling the hours of the day, summoning citizens to meetings, warning of the opening of the municipal courts or simply calling the faithful to prayer at one of Bristol’s many churches.

Marsh Street itself was full of sailors who had either just come ashore, intent on finding

the nearest brothel, or were about to embark on one of the many ships at present riding at anchor along the Backs, laden with wine or soap or some other cargo destined for foreign shores. In front of one of the warehouses which lined the busy wharves was a carrier, loading his cart with bales of cloth which I learned later was woven by the weavers who lived and worked in the suburb of Redcliffe, on the opposite side of the Avon.

The carrier raised his head and, when he saw us approaching, lifted his hand in greeting.

‘You’re late, Marjorie,’ he said accusingly. ‘I’m almost ready to leave. What are my orders this time?’

‘The same as usual. When you get to London, you’re to go straight to the Steelyard. Deliver to the Hanse merchants and to nobody else.’ She turned to me, adding by way of explanation: ‘The Easterlings pay cash, which the Alderman insists on. Londoners want credit, he says, and then try to settle bad debts with all kinds of nonsense, such as tennis balls or packs of cards or bales of tassels.’ She chuckled again, drily. ‘They may get away with that in other parts of the country, but not in their dealings with Bristol.’ She put her hand into the pocket of her skirt and produced a piece of paper sealed with red wax, which she handed to the carrier. ‘And if you’d deliver this for me, I’d be obliged.’ A coin passed between them.

The man nodded cheerfully and tucked the letter inside his greasy, food-stained jacket. ‘Your cousin, is it? Never fear! I’ll see it gets there. What about His High and Mightiness? Payment as usual, I suppose, after the job is done.’

Marjorie smiled. ‘What else did you expect? You know the way the Alderman works as well as I do.’

‘It was worth asking, just in case, one day, a miracle happens. I’ll be off, then. Tell Alderman Weaver I’ll see him in a week’s time, when I get back.’ He nodded briefly at me and disappeared once more inside the warehouse. Further along the wharf, some sailors were acting the fool, lurching perilously close to the edge and singing a drunken shanty. ‘Hail and howe, let the wind blow! The Prior of Prickingham has a big—’

Death and the Chapman

Death and the Chapman