- Home

- Kate Sedley

Death and the Chapman Page 2

Death and the Chapman Read online

Page 2

My companion gave an unconvincing shriek and clapped both hands over her ears.

‘It’s all right,’ I assured her gravely. ‘Has a big toe is what they’re singing.’

‘I dare say. It’s what they mean that matters.’ She added with mock severity: ‘The fools will be in the water in a moment and then they’ll find themselves up before the Watch. However, that’s their lookout, not ours. So, if you’ll give me your arm again, we’ll be off to Broad Street and that meal I promised you. By the way, what’s your name?’

‘Roger.’

‘And mine is Marjorie Dyer. That was my father’s trade. He’s dead now, God rest him!’ She squeezed my arm and shuffled along beside me. ‘I’m sorry to be so slow, but this warm weather affects my legs. Cheer up! Not much farther to go now.’

‘Good,’ I said. ‘It’s been hours since my last meal. I’m starving.’

Chapter Two

I realize that, as yet, I’ve offered no explanation for the political events which were unfolding in Bristol on that warm May morning. Well… politics are boring. As are dates and facts. But in so far as those happenings and their sequel of some months later impinged, however slightly, upon my own story and the unravelling of my first mystery, I feel obliged to paint in the larger background. Briefly. I promise. And I can hardly expect the young tyros of the present generation, in their feverish preoccupation with New Worlds and New Learning, to try to unravel the tangled skein of events which was England in the last century. I knew precious little about it, myself, at their age. What I know now is the result of age, of reading, of piecing together fragments of conversation and knowledge gleaned over many years.

In the year 1399, King Richard the Second was deposed, and eventually murdered, by his cousin Henry of Bolingbroke, who usurped the crown as King Henry the Fourth.

The childless Richard’s acknowledged heir was his cousin, Roger Mortimer, grandson of Edward the Third’s third son, Lionel. Henry was the son of John of Gaunt, a younger son of that same monarch, and from this situation there arose, half a century later, a bloody dynastic struggle.

Richard Plantagenet, Duke of York, direct descendant of Roger Mortimer, claimed the crown from his cousin, King Henry the Sixth, Bolingbroke’s grandson. York was driven to it by the unrelenting enmity of Henry’s queen, Margaret of Anjou, and was supported by his brother-in-law, the Earl of Salisbury, and Salisbury’s eldest son, the Earl of Warwick.

The first blow was struck on 22 May, 1455, and, five years later both York and Salisbury lost their lives at the battle of Wakefield. Six months after his father’s death, York’s eldest son was crowned King Edward the Fourth in Westminster Abbey.

At first, all went well, and this apparently easy-going young man of eighteen showed proper gratitude and respect for the architects of his victory, his mother’s family of Neville, chief of whom was her nephew, the mighty Earl of Warwick.

In the year 1464, however, while Warwick worked tirelessly to bring about a French alliance through Edward’s marriage to Bona of Savoy, Edward secretly married Elizabeth Woodville, the widow of the Lancastrian Lord Grey; a woman five years his senior and already the mother of two sons.

The marriage estranged not only the Earl of Warwick, but also Edward’s brother, George, Duke of Clarence. The King’s youngest brother, Richard, Duke of Gloucester, remained loyal, in spite of his hatred of the Woodville family.

Eventually, in 1469, the Nevilles kidnapped the King and attempted to rule the country through their prisoner. When this failed, Warwick tried to adduce Edward’s bastardy and put the Duke of Clarence, who had married the Earl’s elder daughter, Isabel, on the throne instead.

When this plan also foundered, Warwick, Clarence and their wives, together with Warwick’s younger daughter, Anne, fled to France. Here, the Earl, completely changing his tactics, made peace with the exiled Margaret of Anjou and agreed to restore the imprisoned Henry the Sixth to the throne. Anne Neville was married to Edward of Lancaster, Henry and Margaret’s son.

In the autumn of 1470, the year before my story opened, three months before my mother died, eight months before I walked from Wells to Bristol, Warwick and Clarence returned to England with men and money supplied by King Louis of France. Partly through King Edward’s own folly, he was out-generalled and caught in a trap. With the Duke of Gloucester and a handful of loyal friends, he fled to Burgundy, throwing himself on the mercy of Duke Charles, his sister Margaret’s husband.

Elizabeth Woodville and her three little daughters, together with the Duke of Gloucester’s two young children, sought sanctuary in Westminster Abbey, where the erstwhile queen gave birth to a boy, named after his father.

Then, in March of the following year, Edward of York returned to reclaim his throne. Landing at Ravenspur, he and his youngest brother marched south almost without opposition. At Banbury, the Duke of Clarence joined them, deserting his father-in-law, and by early April Edward was in London.

Warwick, who had been in Coventry, suddenly moved against them, but on Easter Sunday was defeated and killed at Barnet. The next day, Margaret of Anjou, her son and daughter-in-law, landed at Weymouth to be met by the terrible news. Instead of attacking London, the Queen and her army marched north-west in an attempt to link up with King Henry’s half-brother, Jasper Tudor, in Wales, entering Bristol at the end of April. A few days later she learned that King Edward was already at Malmesbury, racing across country to intercept her, and on 2 May, that warm, sunny Thursday when I first heard the name of Clement Weaver, she and her troops left the city in a hurry; in a frantic bid to outpace King Edward.

* * *

We approached Alderman Weaver’s house in Broad Street from the back and the narrow confines of Tower Lane. There was a little walled garden, as I remember, with a pear and apple tree, both thick with blossom, a bed of herbs and simples, a border of flowers along one wall and a lean-to privy. Marjorie Dyer produced a key from the heavy bunch attached to her belt and unlocked the door which led into the kitchen.

This was stone-flagged and strewn with rushes. An iron pot suspended over the fire was obviously full of a stew intended for the family’s supper. An iron frying-pan, a mortar-and-pestle, various ladles and spoons, basins and ewers were grouped together on the wooden table. Sides of salted beef and mutton hung from hooks in the ceiling. It reminded me of my mother’s kitchen, except that it was much bigger. Well, let me be honest. We only had one living-room in my mother’s house. I had never known the luxury of a parlour.

This house, which was several storeys high, no doubt had a buttery and a hall as well as a parlour. And certainly more than one bedchamber. But there again, I knew nothing of bedchambers any more than I did of parlours. At home, I had slept on a truckle bed in one corner of the kitchen, and at the Abbey, in a dormitory with the other novices. This was the first gentleman’s dwelling l had ever been in.

‘Sit yourself down.’ Marjorie Dyer nodded towards a stool near the hearth, covered with a red and green cloth. ‘Leave your pack by the door and I’ll look at it later. I’m short of needles and thread, if you have any.’

I assured her that I had and thankfully slipped the heavy bundle from my back. I had been on my feet almost since sunrise and was beginning to feel tired. I slumped on to the stool she had indicated, keeping well away from the fire. Its heat was intense and the smoke was making my eyes water. As my companion bustled around, she appraised me with her shrewd brown eyes.

‘You’re a big lad. Nearly as tall as King Edward, I’d guess. And they say he stands over six feet.’

‘Have you ever seen him, then?’ I asked her, but with less curiosity than I might have displayed if the warmth hadn’t begun to make me so drowsy. Marjorie handed me a mazer of ale, and the taste of the cold, bitter liquid went some way towards reviving me.

‘A glimpse. Ten years ago when he visited Bristol. Very tall and very handsome, fair-haired, like you, and eyes the same shade of blue. The women all went wild about him.’ She grinned. �

�I reckon there were a few cuckolded husbands during that visit. They say he’s a great womanizer.’

Her tone of voice seemed to imply a question and I glanced up, shaking my head. ‘I’m still a virgin,’ I said. ‘There wasn’t much chance to be anything else at the abbey.’ I had given her a brief history of my life while we were walking from Marsh Street.

She gave a chuckle which slid into a full-throated laugh. ‘That’s not what I’ve heard.’

I shrugged. ‘Oh, I know there are stories about religious houses, and I’ve no doubt there’s a certain amount of laxity in some of them. But we had a particularly strict Master of Novices.’

It was her turn to shrug plump shoulders. ‘You’re young. There’s no hurry.’ Her face shadowed again momentarily, as she cleared a space for me at the table. ‘Although, I shouldn’t say that, I suppose. Youth alone is no guarantee of longevity.’ She motioned me to bring my stool over and went to spoon some of the stew on to a plate.

I got up and, carrying my now half-empty mazer in one hand and the stool in the other, I crossed the room and settled myself at the table. ‘I expect the plague will be rife again this summer.’

Marjorie put the plate of steaming meat and vegetables in front of me. There was also some black bread, a piece of goat’s milk cheese wrapped in a dock leaf, and a dish of those little green and white leeks which can be eaten raw. ‘I wasn’t necessarily thinking of illness,’ she said. ‘There’s… there’s also accident… and… and murder.’ In the sudden silence which succeeded her words, all I could hear was the crackling of the fire.

I swallowed the spoonful of stew which I had shovelled into my mouth and repeated, ‘Murder?’ It had not been just a casual remark, I could tell that by the way she spoke and looked. The word had a special significance for her.

She replenished my mazer from the vat of ale which stood near the door and drew up another stool to the table. ‘Forget I said anything. I shouldn’t be discussing the family’s troubles with a stranger.’

I wiped my mouth on my sleeve. I was pretty uncouth in those days. ‘That’s not fair,’ I protested. ‘You shouldn’t arouse my curiosity and then refuse to tell me what it’s about. Who do you know who’s been murdered?’

Marjorie took one of the little leeks from the dish and began to nibble it. ‘It was just a remark. I didn’t say I knew anyone.’ She glanced sideways at my sceptical expression and capitulated. ‘All right. Although I ought not to say anything, really. And besides, no one’s sure that it is murder. At present, it’s just a case of… disappearance.’

‘Whose disappearance?’ I found myself intrigued, the more so now that my first pangs of hunger had been assuaged. In the distance, through the open kitchen door, came sounds of the bustling city, alive and vigorous in the warm spring weather.

‘The Alderman’s son,’ she said at last, reluctantly, as though wishing she hadn’t spoken. Nevertheless, she went on. ‘He disappeared last winter in London.’

I tore a piece off the loaf of bread. ‘You mean they never found a body? But in that case, what makes you think it’s murder?’

‘The circumstances of his disappearance.’ She leaned forward, folding her plump arms together on the table. ‘There was no reason for Clement to run away – if that’s what you were thinking.’

It was a possibility which had crossed my mind, I had to admit, and I wasn’t going to abandon it in a hurry. ‘How old was Master Clement?’

‘About as old as you. Maybe a little older.’

I considered this information. ‘My mother always insisted that I was born in the same year as the Duke of Gloucester. So… I reckon I’ve seen nineteen summers.’ My companion nodded. ‘That seems about right. Clement would have been about nine when King Edward visited Bristol.’

‘And ten years on, he’s the age when he might well have quarrelled with his father and decided to be his own master.’

Marjorie shook her head. ‘No!’ she said emphatically. ‘Clement got on well with his father, like his sister. The Alderman’s an indulgent father. Over-indulgent, if you want my honest opinion. Ever since his wife died, a year ago last Michaelmas, Alison and her brother have meant everything to him. And now Alison’s getting married he’s going to be very lonely, but he won’t do anything to stand in her way. There’s no talk of postponing the marriage so he can keep her at home a bit longer. And I know plenty of men who would be selfish enough to do that, whatever you might be planning to say in defence of your sex.’

‘I’m not planning to say anything of the sort,’ I protested mildly. ‘I’ve no illusions about people’s shortcomings, whether they’re male or female. Humanity has a lot of failings.’

‘An old head on young shoulders,’ she mocked. ‘That I should live to see the day!’

I ignored this. ‘So Clement Weaver didn’t disappear voluntarily. Didn’t the Alderman make inquiries for him?’

‘Of course he did, you stupid boy! He went to London himself, stayed there for months, with his brother and two of his nephews. They scoured the city from end to end. They even managed to enlist the help of Lord Stanley, but all to no avail. Clement was never found. He just disappeared from the face of the earth.’

I had finished my stew by this time and looked significantly at my empty plate. Marjorie Dyer, somewhat to my surprise, took the hint and rose to fetch me a second helping. ‘You’ll never want for asking,’ she commented drily.

Pointless to say that I hadn’t uttered a word. Meekly, I accepted the refilled plate which she set before me, drained my mazer and attacked the food with relish. When I could speak once more, I said: ‘You’ve intrigued me. Having gone this far, why don’t you tell me the whole story? That is, if you can spare the time. I can see you’re a busy woman.’

‘Mmmm… And I can see you’ve a silver tongue when it suits you. A way of charming the birds off the trees, as my father would have said. And l shouldn’t really spare the time to sit and chat with you. I’ve a junket to make for supper. However, there’s not much to tell, and ten minutes or so won’t make that much difference. Not if you’re really interested, that is.’

I nodded, unable to reply because my mouth was full. But before she could begin, there was an interruption. The door leading from the hall opened and a girl about my own age, or a little younger, came into the kitchen. This, I assumed, correctly as it happened, was the daughter of the house, Alison Weaver.

* * *

She wasn’t a girl you could really call pretty; her nose was too large and the wide mouth a little too decided. But she had lovely eyes, a soft hazel, flecked with green and fringed with very long, very thick lashes. Her skin was honey-coloured, and she had made no attempt to whiten it, as was fashionable. She was thin, with tiny hands and feet, but had a wiry kind of strength which, at second glance, detracted from my first impression of a soft and yielding vulnerability.

‘Marjorie—’ she began, then stopped abruptly. ‘Who’s this?’ she demanded, staring at me and my plateful of stew.

Marjorie, I thought, seemed a little flustered; a little nervous of a girl she must have known since childhood. It was almost as though there were some antipathy between them.

‘He’s a chapman. He gave me his arm as far as Marsh Street because my legs were bad.’ She was defensive, improvising, and sent me a quick, covert glance which told me plainly not to contradict her. And, indeed, it was the truth as far as it went. ‘I was feeling faint and he brought me home. I felt the least I could do was to offer him something to eat.’

The girl continued to stare at me, then nodded briefly. ‘All right,’ she said. ‘As long as you don’t make a habit of it. You know Father’s rules about the servants entertaining strangers.’ I looked at Marjorie and saw the faint stain of red on her cheeks, the badge of her resentment, and wondered fleetingly why she stayed here. A number of reasons presented themselves, but before I could formulate them properly in my mind, Alison Weaver addressed me. ‘What sort of merchandise do you carry?’

/>

I dropped the spoon on my plate and wiped my mouth hurriedly, this time on the back of my hand. ‘I… I have s— some very fine lace,’ I managed to stutter. ‘And some very pretty coloured ribbons. Needles, threads, toys… The usual sort of things,’ I finished lamely.

I could see by her dark green gown of very fine wool, with its trimming of sable, that money was no object to the Alderman when it came to his daughter’s clothing. A coral rosary was wrapped around her left wrist, and a black-enamel and gold cramp ring adorned one finger. She had other rings, some of them set with precious stones, and several gold chains around her neck. It was not difficult to see that her father was a man of substance. I doubted if she would be interested in the sort of things that were in my pack.

As I say, I was young then, and had been out of the world for a number of years. I didn’t appreciate, as I do now, that women can never resist the prospect of buying, particularly if it’s for the adornment of their bodies.

‘Show me!’ she commanded.

I rose hastily and fetched my pack from the corner, while Marjorie Dyer cleared more space on the table so that I could lay out my stock. I had been pleased with it when I bought it off the old pedlar, but it looked little enough now that it was on display. Or perhaps it was simply that I was seeing it as I imagined Alison Weaver was seeing it, appraising it against the goods she could buy in the shops of Bristol and London. But I need not have worried. Without even glancing at anything else, she stretched one thin brown hand instinctively for the best thing there, a length of figured, ivory-coloured ribbon. She held it up to the light, letting it cascade through her fingers in a shimmering waterfall to the dusty floor. For the first time since entering the kitchen, she smiled.

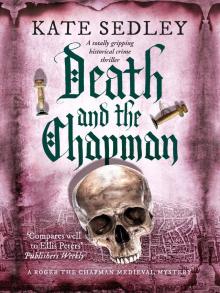

Death and the Chapman

Death and the Chapman