- Home

- Kate Sedley

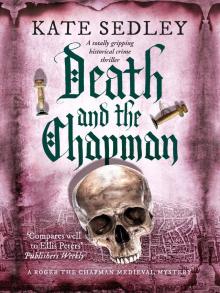

Death and the Chapman Page 8

Death and the Chapman Read online

Page 8

The silence had grown uncomfortable. I nervously cleared my throat and said: ‘As I told your ladyship, I promised Alderman Weaver that on reaching London I would make what inquiries I could for his son, even though, at the time I thought it foolish. Now, however, I feel that there must be some link between both his and your husband’s disappearance and the Crossed Hands inn; enough, at any rate, to justify my taking an interest in the place. If I discover anything, I will inform you.’

With an effort, Lady Mallory stopped fidgeting, clasping her hands together in her lap. The firelight turned the silk of her robe from black to plum to amber.

‘I should be grateful for any news of Sir Richard.’ She spoke stiffly, and I could see that the idea of being obligated to a common chapman did not please her. But, like Alderman Weaver, she realized that I had advantages not enjoyed by her servants nor even by the Sergeant of the Watch. No one would suspect me of over-much intelligence nor of having any interest in her husband’s disappearance. I was in a position to make inquiries without actually seeming to do so, and might also pick up scraps of information which would give me a clue to his fate.

I rose from my stool and made her a bow. ‘That is agreed, then. And now, I must take my leave. It’s dark and I have a long walk back to Canterbury.’

She said reluctantly: ‘You must have food and drink before you go. Bess! Take your friend to Robert with instructions to feed him, then come straight back here. I want you to brush my hair before I go to bed. And you can find Matthew for me. I need him to sing to me before I sleep.’ Lady Mallory shivered suddenly, as though someone had walked over her grave. ‘I shall ride the nightmare, otherwise.’

Bess came across and curtseyed demurely, but it was obvious from her expression that she was disappointed by the command for her immediate return. She had had hopes, that girl, as I had, of a fond and protracted farewell. But it was not to be. With a pout of resignation, she inclined her head in my direction and said: ‘Come with me.’

* * *

The steward’s room was next to the buttery at the back of the house, and was furnished as befitted his exalted status among the household servants. A fire burned on the hearth beneath the carved stone mantelpiece, which was painted red and blue. The rushes covering the floor had obviously been fresh that morning: no stale odours arose from them, such as would have been noticeable after one or two days. A long table stood in the centre of the room, and, in addition to a couple of benches, there was also a single armchair, old and blackened, it was true, but carved from good, solid oak. Tallow candles flared in the iron wall-sconces, sending shadows across the scarlet and white painted walls. A comfortable room for a steward; perhaps just a little too comfortable. I recalled Bess’s words concerning Robert’s aspirations. Maybe they were founded on firmer ground than she had thought. Maybe Lady Mallory had given him reason.

Robert was none too pleased to be made personally responsible for my welfare. When Bess had delivered both me and her mistress’s instructions to him, he looked annoyed, giving me one of his high-bred stares, which he plainly copied from my lady.

‘Surely,’ he protested, ‘this… this person can be seen to in the kitchen.’

Bess turned on her heel with a provocative swing of her hips. ‘Those were my instructions. I am simply the messenger. But you would be unwise to disregard them.’

She sent me a farewell glance across her shoulder, fluttered the long dark eyelashes and then was gone. Robert and I were left facing one another.

‘You’d better sit down,’ he said at last, indicating one of the benches drawn up to the table. He went to the door, opened it and yelled a name into the draughty corridor. After a lapse of some moments, a young boy appeared, knuckling the sleep from his eyes. The steward cuffed him. ‘Dozing again, in front of the range? Tell Cook to prepare some food and ale for the chapman here. My lady’s orders. Bring it in here when it’s ready. Now, get along with you, and don’t be all night about it!’

The lad was clearly glad to escape and vanished swiftly. Robert seated himself in the armchair and tried to ignore my unwanted presence. He, too, I judged to be of some thirty to thirty-five summers; a little older, possibly, than his mistress. He had sandy hair, and was not unhandsome if one overlooked a tendency to baldness. His high-bridged, aquiline nose was the strongest feature of a thin, almost cadaverous face, giving his features a misleading strength of character. But vanity sat in the pale blue eyes and gave him his dominant expression.

There was silence between us until the boy returned, bearing a mazer of ale in one hand and a loaded platter in the other, both of which he set down on the table in front of me. Then he slithered quickly from the room before there was time to incur any more of the steward’s bile. I addressed myself eagerly to the food. It was some hours since I had last eaten and I had not realized just how hungry I was.

There were several slices of thick black bread, cheese and butter, wrapped in dock leaves. A small bowl containing blackberries sweetened with honey, and a slice of curd tart flavoured with ginger and saffron completed the meal, which I munched my way through with relish. The cook had done me proud, considering that I was only a common chapman who could hardly expect distinguished treatment. Robert stared doggedly into the fire while I ate, but as I lifted the mazer of ale to my lips, he finally condescended to address me.

‘What was your business with my lady?’

I toyed for a minute with the idea of misleading him; pretending that Lady Mallory had wanted to buy some of my wares. Then I recollected that I did not have my pack with me. I had left it in what I trusted were the safe hands of the Hospital Warden. After a few seconds more of deliberation, I decided to tell the truth. Robert would probably learn it from Bess, if not from Lady Mallory herself, eventually.

So the story was repeated yet again, from my encounter with Marjorie Dyer in Bristol through to this present evening and my meeting with his mistress. I felt sometimes as though I could tell parts of it in my sleep.

When I had finished, Robert pursed his lips and frowned. ‘My lady wants him found, does she?’ he asked, referring to Sir Richard.

‘Does that surprise you?’

He shrugged, realizing that he had either given too much away or created the wrong impression, and hastened to put matters right.

‘I should have thought it obvious, after all these weeks, that Sir Richard is dead. I am merely surprised that my lady has consented to you wasting your time.’

I glanced at him and saw that he spoke more in hope than from any deep conviction. Nevertheless, the assumption of his master’s death was a reasonable one, unless he knew of circumstances which made it improbable. I probed gently.

‘Is it possible that Sir Richard could have had a leman in London, with whom he might have wished to elope?’

The steward gave this idea short shrift, and rightly so. ‘Leaving everything he valued most behind him? His house, his clothes, his worldly goods! Your wits are wool-gathering! What leman is worth such a sacrifice? My master could have spent as long as he wished away from home, so my lady knew of his intentions. No, no! Some ill has befallen him on the journey home. There is no other explanation.’

I shook my head as I swallowed the last of my ale. ‘You forget. The horses were left at the Crossed Hands inn. Whatever happened to Sir Richard and his servant befell them in London, as it did to Clement Weaver.’

The steward was not interested in the fate of Clement Weaver, pursuing thoughts of his own.

‘Besides, Sir Richard was not a man for womanizing. I doubt if he was ever unfaithful to my lady.’ Nor of much use to her either, his tone seemed to imply, but I made no comment. Robert continued: ‘His passion was wine. He would travel miles, brave all hazards, to taste a recommended vintage. His people were vintners, two generations back, who made their fortune and married into the nobility. Not that there’s lack of precedent for such a happening. Geoffrey Chaucer’s father was a vintner, and Chaucer’s granddaughter married the

Duke of Suffolk. And the present duke, Chaucer’s great-grandson, is married to no less a personage than the present king’s sister.’

I noted a predatory gleam in his eye. If such things could turn out so for one family, why not for another? If his lady really were a widow, there might be hope for him yet.

I got reluctantly to my feet. The warmth of the fire was pleasant and I had no wish to leave it, but I had to be on my way. Roused from the contemplation of a rosy future, the steward turned his head, becoming once again aware of my existence.

‘You’re going? You’ll be sleeping in a ditch tonight,’ he added, not without a certain satisfaction. ‘Curfew’s past. The city gates will be shut.’

I smiled maliciously. ‘Oh, there are ways and means of getting into a town after dark, if you know them. Then one only has to avoid the Watch…’ I winked conspiratorially.

His thin face assumed a prim expression. Plainly he felt that one who had so nearly embraced the religious life should be above breaking the law. He asked: ‘What have you decided with my lady?’

‘I’ve promised her that I’ll try to discover what has happened to her husband, and send her word if I do.’

‘And what do you think are your chances?’

‘Of finding out the truth?’ I considered the question. ‘More, perhaps, than I thought when I made a similar promise to Alderman Weaver to try to find out what happened to his son. Now, at least, I feel that the Crossed Hands inn may be central to the mystery. It’s the place to begin my inquiries, at any rate.’

The steward nodded. ‘And what do you think are the chances that Sir Richard might still be alive?’

There was the sharp smell of a candle as it guttered and died. The shutters were still open to the warm night air, and I could see a thin, ragged slip of moon hanging low over the distant trees. ‘If you want my honest opinion, none,’ I answered, trying to ignore the sudden flicker of relief in the pale blue eyes. ‘I think he and Jacob Pender and Clement Weaver are all dead, but how, and by whose hand, I have as yet no idea.’

‘And motive?’ Robert asked. ‘What do you say to that?’

I hesitated, unwilling to commit myself, but with so little doubt in my own mind, I was forced to admit: ‘Robbery. Sir Richard was a wealthy man and Clement Weaver was carrying a large sum of money about his person.’

The steward frowned. ‘But surely you told me earlier that no one was aware of that fact, except his father. Not even his sister.’

I was suddenly very tired and my mind felt dull and stupid. I needed to forget this problem for a while and sleep. In any case, there was nothing further I could do now until I got to London. I determined to set out as early as I could the following morning, but before that, I wanted my bed and the spiritual refreshment of solitude. I lifted my stout ash stick from the floor where I had laid it.

‘I really must be on my way,’ I said. ‘I don’t know the answer to this puzzle yet, and I may never do so. Maybe your mistress would do better to place her reliance in the officers of the King, as would Alderman Weaver. Nevertheless, I shall do what I can and perhaps God will crown my endeavours with success.’

I held out my hand in farewell, but could see at once that I had affronted Robert’s dignity. He was a steward and did not shake the hand of a lowly chapman. It dawned on him, too, that for the last half-hour he had been talking to me as though I were his equal, and he shrank back in his chair as though contaminated. I let my arm sink slowly to my side again, not bothering to disguise my contempt. He did at least get to his feet and summoned the boy to show me out, but that was to ensure that the house was properly locked and barred after my departure.

I made my way along the track, dimly discernible in the darkness, swinging my cudgel vigorously to discourage attacks from lurking footpads or other prowlers. I was glad to shake the dust of Tuffnel Manor from my feet. Apart from Bess, I had formed no favourable opinion of its inmates and thought it an unhappy household. That did not mean, however, that I would do less than my best to discover what had happened to Sir Richard and Jacob Pender.

* * *

I learned much later that had I waited another twenty-four hours in Canterbury, I should have seen King Edward and Queen Elizabeth, together with many of their courtiers, on yet another visit to St Thomas’s shrine. (With hindsight, I should guess that the King’s conscience was troubling him over the necessary death of his cousin and enemy, the late King Henry.) Even so, there was much talk of the royal family among a group of pilgrims returning to London, with whom I travelled the last part of the way. And once again I heard the name of Lady Anne Neville.

The pilgrims were poor and on foot, like myself, and I had fallen in with them some six or seven miles outside the capital. I had spent a congenial morning discussing with a priest from Southwark William of Ockham’s theory that faith and logic could never be reconciled, and that therefore ecclesiastical authority was the sole basis for religious belief.

‘If faith and reason have nothing in common,’ I argued, ‘then God can literally move mountains. Reason tells me that it cannot be done, but William of Ockham insisted that belief is not rational. Yet that means that religion is beyond logic and not subject to the laws which govern nature. I find that difficult to accept.’

‘But, my son, you must believe in the miracles of Christ,’ my companion protested, shocked, ‘and in the absolute authority of Mother Church.’

I grinned. ‘So I have often been told, Father, but somehow or other, there are always too many questions to which I can find no satisfactory answers.’

A silence succeeded my words while the priest marshalled his forces to deal with this Doubting Thomas. And in the quiet, I caught snatches of a conversation in progress behind me between two women, who, I had decided in my own mind, were mother and daughter. They looked sufficiently like one another to give credence to this theory.

‘…Lady Anne Neville,’ the younger woman was saying, and immediately the name attracted my attention. Once more, I was back in Bristol, watching that unhappy child ride along Corn Street. ‘It’s common gossip that the Duke of Clarence doesn’t want his brother to marry her because it will mean the division of the late earl’s estates. As husband to the elder daughter, he hopes to get them all. Or as many of them as he legally can.’

‘A downright wicked shame,’ her mother answered warmly. ‘It wasn’t my lord of Gloucester who deserted King Edward in his hour of need.’

‘Oh, the King intends Duke Richard to have Lady Anne, you may be sure of that. But amicably, if possible, with my lord of Clarence’s and Duchess Isabel’s full consent.’

The girl spoke with that assurance I have frequently noticed among the very poor when talking of royal affairs.

And indeed, more often than not, time and events prove them correct. I have pondered the reason for this, and have come to the conclusion that it is because their own existences are so uninteresting and drab that they live vicariously through others more glamorous than themselves. They look and watch and listen, hoarding scraps of information as some of their fellows hoard money, assessing, interpreting and making valid judgements.

‘It would be a good match,’ the older woman agreed, ‘and please the people. Please themselves as well, no doubt, for they’ve been friends since childhood, and that’s a fact. Brought up together in the North, and always intended for one another by her father…’

I could overhear no more. The priest was speaking again, invoking the teachings of St Augustine in his argument and desperately trying to convince me that obedience was all. I answered randomly, letting him think that he had won our battle of words, too excited now to think of anything but that I was at last within a mile or so of London, that city whose streets were reputedly paved with gold, and which had seen the making and the breaking of so many better men than I. According to my informants who had been there, it was so much bigger, dirtier, noisier, wickeder, more beautiful, more exciting, more interesting than anywhere else in England – so

me people said than anywhere else in Europe – that my heart was beating almost suffocatingly in anticipation. And towards evening, with the sky trailing great ragged banners of blood-red, amethyst and flame, when the distant trees netted the final rays of the sun and seemed to catch fire from within, I saw London for the very first time, lying like a smudged thumb-mark on the horizon. Somewhere inside those walls lay the answer to the riddle of Clement Weaver’s and Sir Richard Mallory’s disappearance. Whether or not it would ever be solved was now up to me.

Part Three

October 1471

London

Chapter Nine

Old age is not simply a matter of rheumatic joints, defective eyesight and impaired hearing; it’s waking up one morning and realizing that there is no longer any future. That is a lesson I have learned these past few years, and something which young people find very hard to grasp. They have life, love and adventure spread before them, without any hint of their own mortality.

I was exactly the same myself, on that early October day in the year of Our Lord 1471 when I crossed London Bridge and entered the city proper for the very first time. It was, as I recall, a morning of frost and needle-sharp sunlight, all white and gold. Everywhere there was brilliance and light, from the sparkle of rimed branches and rooftops to the glitter of the rutted road and the sun-spangled glint of horses’ harness. I was young, strong and ready to take on the world. The thought of any personal danger in the quest which lay in front of me never so much as entered my mind.

Death and the Chapman

Death and the Chapman