- Home

- Kate Sedley

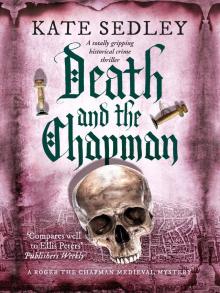

Death and the Chapman Page 10

Death and the Chapman Read online

Page 10

‘You ain’t goin’ in there?’ Philip Lamprey queried in my ear.

I jumped. In my all-absorbing interest I had forgotten my companion, still dogging my footsteps, and who was now peering over my shoulder into the courtyard of the inn.

I wondered how I could shake him off. It seemed ungrateful to abandon him, but I salved my conscience by reflecting that I had bought him a meal in exchange for such information as he had been able to give me. Now, however, I needed to be on my own, with no curious stranger at my elbow. But there might be one more service he could render me.

‘Do you know this Martin Trollope by sight?’ I asked him.

He shook his head. ‘Naow! Only ’eard of ’im by repitation.’

I held out my hand in a gesture of farewell too marked to be mistaken.

‘I must be on my way. God be with you.’

He took his dismissal in good part, clutching my extended hand in his small dry one so firmly as to leave his fingermarks momentarily imprinted on my skin.

‘God be with you, too, friend,’ he rasped hoarsely. ‘If you’re stayin’ in London fer a while, we may meet again sometime. If you ever want t’ find me, I sleeps most nights in St Paul’s churchyard. If it ain’t pissin’ with rain, that is. On the other ’and, if I’ve ’ad a good day’s takings, I might be in one of the Southwark brothels.’ He winked. ‘Good sport there, jus’ s’long as you don’ catch the pox.’

It occurred to me that this must be the reason he spent some of his meagre income on bathing. The Southwark stews were probably not the most salubrious of places and he was afraid of becoming infected. Not that most people considered washing to be a remedy for anything: in fact, many held that immersing the naked body in water was positively dangerous. My mother had, however, never been of that persuasion, and had insisted on my taking regular baths from a very early age, even if it was only in one of the local streams, or standing shivering in the yard of a morning while she threw a bucket of ice-cold water over me.

‘I’ll remember that,’ I said, adding as an afterthought: ‘Where’s your pitch for begging?’

He shrugged. ‘I don’t ’ave a pitch. I jus’ asks where and when I can. But London ain’t that big. You may see me around.’

‘Big enough for me,’ I answered feelingly, and he grinned. Then, swinging smartly on his heel, some of the old military discipline showing in his step, he turned once again into Thames Street, where he was soon swallowed up by the crowd. I was left standing outside the Crossed Hands inn, not quite sure what to do next or where to begin the inquiries which I had so rashly undertaken. And I had my living to earn, as well.

The sun was high overhead, but there was still a nip in the air, and I recalled the frost of that morning. It would be sensible, perhaps, to make sure of a billet for the night by a warm fire, rather than embark immediately on any inquiries. Besides which, I had not yet made up my mind what form they should take nor how I should approach the matter. A chapman could hardly walk in and start asking questions about Sir Richard Mallory and the son of Alderman Weaver without arousing suspicion. And suspicion was the thing I most wished to avoid if I were to stand any chance of unravelling this mystery. It would be best, therefore, if I presented myself at the Baptist’s Head and made myself known to Thomas Prynne as an acquaintance of Marjorie Dyer, throwing myself on his hospitality for a corner to sleep in, where I should not be in the way of his guests.

I hitched my pack higher on to my back, grasped my cudgel purposefully and turned to walk on down the street.

As I did so, I happened to glance upwards, to a window on the right of the archway, which looked out over Crooked Lane. It was open slightly, and I was suddenly aware that someone, whether male or female I could not tell, was standing, a little withdrawn from the aperture, in the passageway beyond. While I watched, the figure made a forward movement, as though to open the casement wider, but as it did so a voice shouted: ‘Get back!’ and, almost at once, the window was closed.

* * *

Alison Weaver and Philip Lamprey had both been correct in their information: the sign of the Baptist’s Head could plainly be seen on the other side of the alley from the corner of Thames Street and Crooked Lane, and one side of the inn did indeed overlook the river. Crooked Lane itself was not a long street, and, apart from the two hostelries, was walled in by tightly packed houses, whose upper storeys almost met in the middle. Today, a little thin sunshine filtered between the overhanging eaves, but in cheerless weather it must, I thought with a shiver, be gloomy indeed. There was, strangely enough, no twist or bend of any kind in the road, and I wondered how it had come by its name. The customary mounds of refuse were heaped outside of doorways, while the narrow channel separating the cobbles on either side of the street was full of rainwater and rotting food. The carcass of a dead dog lay on somebody’s doorstep. This, in London no doubt as in other towns and cities, was a serious offence, and the owner of the animal could be heavily fined.

The Baptist’s Head was entered directly from the street, not built, like its rival, around a courtyard. It was far smaller than the Crossed Hands, and, because of its location, less likely to be the recipient of passing traffic.

People who stayed there would know its reputation by word of mouth from other, satisfied fellow travellers. Its timber front looked clean and well painted, and the front door, which stood open, emitted delicious smells of cooking. Beef and dumplings, I thought, my appetite whetted. Whatever lucky person took supper here tonight would not go hungry. I stepped inside.

I was in a flagged passageway which ended in another doorway at the far end, also standing open to the light and air. Yet more doors flanked me on both sides, and a narrow twisting stair led to the upper storey. I wondered where they stabled the horses. This thought was answered a moment later by a high-pitched whinny and the shifting of hooves from the back of the inn. I walked the length of the passage and, sure enough, there were three stalls beneath a lean-to roof, together with piles of hay and fodder, facing me across a cobbled courtyard. Further investigation revealed that the yard was reached from Crooked Lane by an alleyway running along by the Baptist’s Head on the side furthest from the river. A horse, a big red roan, occupied one of the stalls, but the other two were empty. Trade was not brisk, it seemed; not, at least, for the moment.

I went back inside, but still there was no sign of anyone. The ale-room was uninhabited, but dinner had been recently served. Dirty plates and mazers scattered around the tables testified to the fact, while the absence of left-overs confirmed my impression that the food here was good. The smell of the stew was making my mouth water, even though I had recently eaten. I returned to the passage and hollered.

‘Is anyone about? Thomas Prynne! Are you there?’

There was a muffled answering shout from somewhere beneath me. Then a trapdoor in the floor of the ale-room was flung back with the resounding clatter of wood hitting stone, and a man came up the steps from the cellar.

‘Sir, my apologies,’ he began, but stopped when he saw me. ‘Who are you?’ He noticed my pack and waved a dismissive hand. ‘I’m sorry, but there are no women here just at present to be needing your gew-gaws.’

He was a short, powerfully built man, with a barrel chest, well-muscled arms and thighs, a thatch of grey hair and a network of fine wrinkles raying the weatherbeaten skin. His eyes, which were of a bright cornflower blue, had a twinkle in them, and his whole person radiated a contentment with life in general, and his own existence in particular, which was very reassuring. This, I thought, was a happy man.

‘Thomas Prynne?’ I queried, although I was sure of his answer.

‘Yes. But I’ve already explained—’

‘I’m not here to sell you anything,’ I cut in quickly. ‘A friend of yours, Marjorie Dyer, told me to look you up if I was ever in London.’

‘Marjorie Dyer? Of Bristol?’

‘The same. Also Alderman Weaver mentioned that you might be persuaded to give me a corner to sl

eep in for the time that I’m here.’

‘Alfred Weaver?’ he demanded incredulously. The eyes twinkled more than ever. ‘He said that? Now what in heaven’s name would one of our leading Bristol Aldermen be doing talking to a chapman?’ The West Country accent was still very strong.

I grinned. It was obvious that Thomas Prynne had the measure of his old boyhood friend.

‘It’s a long story,’ I replied. ‘Not one to be told in a moment. Later, perhaps, when you have more time. I’m off to the Cheap presently to sell my goods, if I’m lucky. But I’d like to be sure of a night’s lodging first. I can pay my way if the accommodation is not too fancy.’

Thomas Prynne shrugged. ‘Any friend of Marjorie’s can have a bed here for nothing, and welcome. We have only one visitor at present. Another is expected later this evening, but that leaves a room empty. It’s yours until we need it. Then, if you’re still here, you may sleep in the kitchen for as long as you like.’ He smiled, the lines deepening around the corners of his eyes. ‘But I shall expect you to take your food and ale here.’

‘Judging from the smells coming from your kitchen that won’t be any hardship,’ I answered cheerfully. ‘But Marjorie Dyer and I have only a passing acquaintance. I shouldn’t wish to take advantage of your generosity without making that plain.’

Thomas regarded me steadily. ‘You know, you’ve aroused my interest. Why should such a brief encounter have caused her to mention my name?’ He indicated one of the barrels ranged around the walls. ‘I have an excellent ale which I don’t hand out to everyone. Surely, you can delay your visit to the Cheap long enough to sample it with me and satisfy my curiosity at the same time. There are still sufficient hours of daylight left for you to sell at least some of your goods.’

I hesitated, feeling that I had already wasted enough precious hours that day, but in view of his most kind offer of free lodgings, what choice did I have but to comply?

I moved to one of the long wooden tables near the old-fashioned, central hearthstone and sat down. I noticed how beautifully clean everything was, the table-tops scrubbed, the sawdust and scattered rushes on the floor freshly laid.

‘I’ll answer any questions you want to ask,’ I said.

* * *

When I was a child, on winter nights, when the door of our cottage was shut against the darkness outside and there was little else to do but sleep, my mother would sing to me. One of the songs I remember best was of the sort where you keep repeating the words you have sung before, but adding a little extra information each time. I reflected that my story was getting like this, growing in length with each retelling, so that now, it took me almost half an hour before I reached my arrival in London. Fortunately, Thomas Prynne was an excellent listener, giving me his full attention and not interrupting with unnecessary questions or exclamations of wonder and astonishment. When I had finished, however, he did permit himself a long, low whistle.

‘A very strange story. You intend to keep your promise to Alfred Weaver, then?’

I twisted my cup of ale between my fingers. ‘I have to confess that I had all but forgotten it by the time I got to Canterbury. If the truth be told, I thought the Alderman’s idea that I might be of some assistance extremely foolish. I thought – I suppose I still do think it possible – that Clement Weaver fell a prey to footpads.’ I could see by Thomas Prynne’s vigorous nod of the head that this was his own opinion. ‘But what happened in Canterbury made me less certain. It also seemed that God meant me to take a hand.’

My companion looked dubious. ‘There is such a thing as coincidence, a more frequent occurrence than you might at first imagine.’ He added: ‘Young Clement’s disappearance was a terrible thing, but robbery and death are not uncommon in London.’

I frowned, watching him pour more ale into my empty cup. ‘The point is, we don’t know for certain that Clement’s dead. And that is what bothers me. Why would footpads take the time and trouble to remove the body?’

Thomas Prynne grimaced. ‘A difficulty, on the face of it, I grant you. But there might be reasons. Perhaps, with winter coming on, they were desperate for clothes. Perhaps they were disturbed, or thought they might be disturbed, before they could safely strip the body, so they carried it away. Not as much of a problem as it seems, if there was more than one of them. And these fellows often work in gangs.’

The need for clothing was something I had not previously thought of. But even so, if the robbers had money, they could buy clothes. And there was still the disappearance of Sir Richard Mallory to be considered. I shook my head.

‘I’m convinced,’ I said, ‘that there’s some mystery about the Crossed Hands inn. Do you know anything of Martin Trollope?’

‘I know him by sight, naturally, and to give the time of day to. Other than that, we have little contact. We are, after all, rivals for custom in the same street.’ Thomas smiled ruefully. ‘And all the advantages are on his side. Location, size, royal patronage and connections…’

‘Tenuous ones, if my information is correct.’ What was it Bess had said? ‘Trollope is merely the cousin of a dependant of the Duke of Clarence.’

Thomas laughed outright at that. ‘It’s easy to tell, Roger Chapman, that you haven’t long been in London. Such a “mere” connection is not to be sneezed at. A great deal of trade at the Crossed Hands is by recommendation from the Duke himself. I wish I could boast as much in the way of royal support.’ He sipped his ale, regarding me thoughtfully over the rim of his cup. ‘So! What do you intend doing by way of fulfilling your promise to Alfred Weaver?’

‘I don’t know yet,’ I admitted. ‘I haven’t as yet decided on a plan of action. But something may occur to me.’

‘I’m sure it will,’ Thomas assured me drily. ‘You seem a very resourceful and competent young man. A chapman who can read and write! Well, well! Wonders will never cease. I can read a little, myself, but putting pen to paper is a skill I have never mastered. I have to rely for that on my partner, Abel Sampson.’ I must have looked surprised, because he laughed. ‘Did you think that I run this place single-handed?’

‘No. No, of course not. I just hadn’t thought about it at all, I suppose. As I’ve already told you, Marjorie Dyer and I had only the briefest of acquaintances. You’re not married?’

Thomas shook his head. ‘I’ve never felt the need. My experience is that wives are generally a hindrance. There are plenty of women for the having in any city, but especially in London. I learned to cook when I was landlord of the Running Man, and with only three bedrooms, not all of which are occupied at any one time, the demands on me are not excessive. Abel and I are our own cellarers, servers and chamberers. That way, with no other wages to pay, and no dependants, we manage to make a living. It’s not easy, but at least the place belongs to us, whereas in Bristol the Running Man was the property of St Augustine’s abbey, and all my efforts simply resulted in the Church getting richer, with no reward to myself.’

‘You deserve to do well,’ I said, adding fervently: ‘This ale is the best I’ve ever tasted and, as I remarked before, the cooking smells delicious.’

‘You shall sample it tonight, when you return from the Cheap.’ He rose to his feet, picking up our empty cups. ‘As for our ales, and especially our wines, Abel and I do the buying ourselves. The ships from Bordeaux tie up west of the Steelyard, at Three Cranes Wharf. It means early rising to be ahead of the vintners, but we don’t begrudge that extra effort. In time, we hope to gain a reputation for selling the best wines of any inn in London.’

I was beginning to admire this man more and more. He was plainly determined, against the odds, to make a success of his venture; and he had all the Bristolian’s canniness with money which should enable him to succeed. He also had humanity and a vein of humour which I found attractive, and I wished him well.

‘When I return this evening,’ I said, ‘I should like to talk to you about the night Clement Weaver disappeared. If you can spare the time, that is.’

; He smiled down at me. ‘We’re expecting another guest, as I told you, but he’s been on the road from Northampton for the past few days, and according to the carrier who brought his message, doesn’t anticipate being here until late. So, if the opportunity arises…’ He broke off with a shrug. ‘Our other guest, by the way, you’ll meet at supper. An impoverished gentleman who is rapidly becoming poorer yet on account of all the litigation he’s involved in. He’s come to London for the second time this year to petition the King. Something to do with land and a contested will.’ He sighed, as if for the folly of the human race. ‘London is full of people like him, pouring their money into the pockets of the lawyers.’

I nodded. I remembered seeing them earlier that day in St Paul’s cloisters.

A step sounded in the passage outside, and a moment later, a tall, thin man appeared in the open doorway of the ale-room. Thomas Prynne nodded towards him.

‘This is my partner, Abel Sampson.’

Chapter Eleven

A second glance showed me that Abel Sampson, though tall, was not so tall as I was. (I use the past tense here because, with the passage of time, I have become a little stooped. Arthritic limbs have inevitably taken their toll.) He was, nevertheless, a considerable height, standing well over five-and-a-half feet, the top of his head reaching to the level of my eyebrows. It was his slender frame which made him appear taller than he really was. I don’t say he was emaciated, but he was certainly extremely thin, and the contrast he made with Thomas Prynne was almost ludicrous. I had to school my features rigorously to prevent them breaking into a grin.

Death and the Chapman

Death and the Chapman